Karamon Gate Shinto Temple Nikko

A few years following the introduction of photography (ca. 1843), Japan endured a radical transition known as the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912). During this time, a popular type of photography, known as tourist photography, emerged and was driven by an increased demand from Western audiences for “traditional” Japanese images. We see in this seemingly staged photograph, six figures posed in front of the Karamon Gate at a Shinto Temple. What encompasses these figures in the foreground are trees/forests and a structural entity associated with religion. This image fits nicely within the context of tourist photography, as what is deemed “traditional” quite often is tied with religion in Japan.

The Yomeimon Gate Shinto Temple Kikko

Yomeimon Gate to Shinto Toshogu shrine still stands today. Nikko is located North of Tokyo in Tochigi Prefecture. This site is also the mausoleum of the founder and first shōgun of the Tokugawa shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu. The temple itself was built in the 17th century, much of the carving work done by the potentially mythical Hidari Jingoro, a revered artist from the Edo period. The gate or torii in the foreground marks not only the entrance to Toshogu but also the change from mundane to sacred. Chosen as a “view” subject for a tourist photography studio, this is indicative of foreign and domestic recognition of the importance to Japan’s recent history in the face of changing times of modernization intertwined with Western aestheticism.

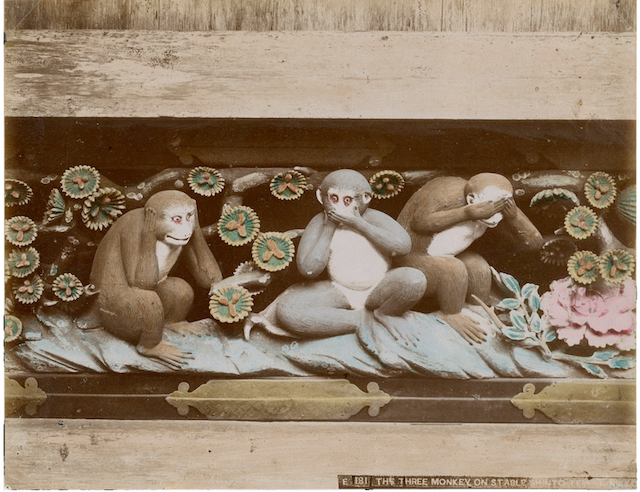

The Three Monkeys on Stable, Shinto Temple

Similarly to the first photo at Nikko shrine Toshogu, this carving remains famous even today. The three wise monkeys carved into the stable represent the proverb, “hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil” meaning that a person should conduct themselves in a manner that is always conscious of self. Originally, the phrase is said to have come from China, however, is also seen in other cultures and religious mediums like the Bible as well. In the Japanese version of this, each monkey is named, starting from left to right, Kikazaru, Iwazaru, and Mizaru. The carving, as well as the rest of the shrine itself, has been attributed again to Hidari Jingoro. The physical location of the carving is also located within the middle of the shrine grounds.

The Tomb of Shinto Temple Nikko

The tomb portion of the photo’s title refers directly to that of Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616). A photograph marking the grave of a prominent historical leader in Japanese history attests to the fascination of the West with the previously isolated country, perhaps exotifying it to some extent. This could even suggest the death of the old Japan at the birth of the new nation. The view from the side of the tomb emphasizes the meaning of the sacred space. As a tourist photograph, the intended audience is not the Japanese or those to whom the grave holds meaning. Rather, it is the Western foreigners who are visiting the space and country as a whole for leisure, interest, and spectacle. This photo marks the end of the walking path of the shrine’s grounds.

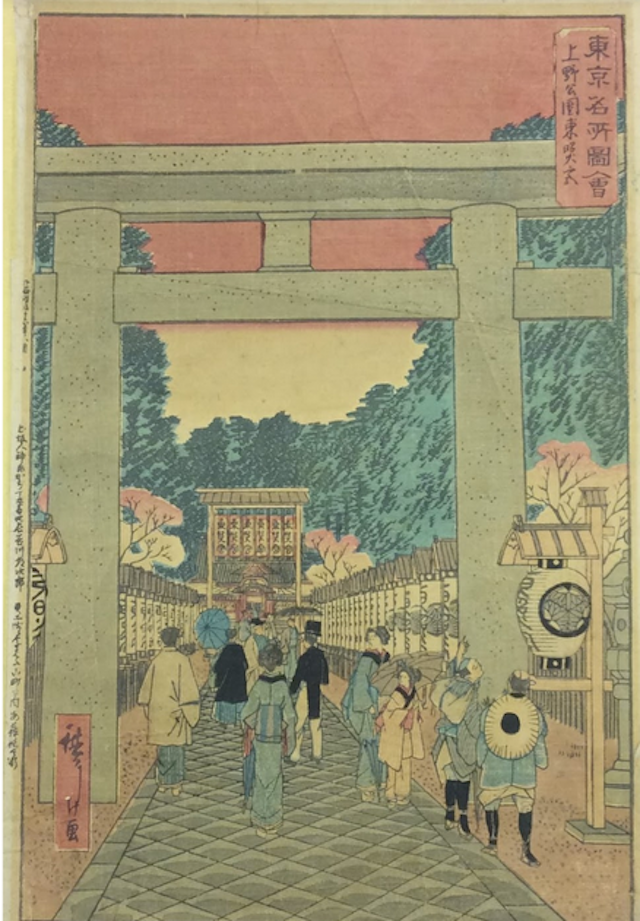

Woodcut of Torii and Worshippers

Scholars and worshippers have acknowledged the role of torii as gateways to the kami, or deities of nature. Most commonly found at the entrance of or within Shinto shrines, the torii symbolically marks the transition from the secular to the sacred. Often made from wood or stone, torii differ in style and shape, but are somewhat uniform with respect to color. Torii gates are usually red (or burnt orange) or white. The red-painted gates not only appeal to the eye, but the color itself symbolizes protection against evil and vitality, and, practically speaking, acts as a preservative. In this image, we see people approaching what seems to be a temple, preparing to partake in an event pertaining to religion.

The Nio Gate Buddhist Temple at Nikko

Nature is highly respected in Japanese culture, as there often exists a deep spiritual bond between those practicing both Buddhism and Shinto and nature’s inescapable presence. In this image, a figure is captured gazing at the Nio Gate, within the context of how powerful their surroundings are. The figure’s gaze expresses the belief in existing harmoniously with nature. The way in which the figure is situated in the image also connotes this inescapability characteristic. Upon glancing at this image, the eye is drawn to the Nio Gate, situated in the middle of the page, yet somewhat in the background. The eye then wanders to the figure, and it then becomes quite obvious that the figure is captivated and consumed by everything within the frame of the photograph.